Australian healthcare practitioners are increasingly using generative artificial intelligence (‘Gen AI’) programs to assist them to manage their administrative and clinical workloads.

In this Insight, we provide guidance around the use of Gen AI in clinical practice and identify liability risks that practitioners may face if they choose to use it.

What is Gen AI?

Gen AI is an advanced, but emerging form of AI that uses supercomputing to create new digital content, not simply to perform or automate a task. Perhaps the most well-known is ChatGPT-4, a Silicon Valley software that produces human-like responses to questions asked, or prompts made, by the user.

In healthcare, the three main forms of Gen AI relevant to practitioners are:

(1) AI Medical Scribes: advanced dictation programs that convert a recording of a consultation into a clinical note

(2) AI Medical Search Engines: sophisticated depositories of medical journals and advice, and

(3) Large Language Models (‘LLMs’): AI systems that generate human-like written text responses to questions, including medical questions.

Gen AI versus medical AI technologies

Gen AI differs to medical AI technologies that are used to directly treat a patient, such as computer-aided X-ray imaging programs that use AI to interpret radiology and identify tumours. These devices are regulated as ‘software-based medical devices’ by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)[1]. However, Gen AI, is not.

Unlike medical AI technologies, Gen AI has a general, rather than a patient-centred, application. Therefore, practitioners who use Gen AI systems must understand that they do so as private users, not as practitioners using an approved medical software that has a widely-accepted application in healthcare.

Healthcare quality and patient confidentiality

Several government discussion papers have submitted that using AI to automate administrative tasks could reduce medical practitioners’ workloads by 30%.[2] However, most healthcare organisations are concerned about the risk that Gen AI could be misused or over-relied upon to the detriment of healthcare quality and with risks to patient confidentiality.

The Risks of Using AI Medical Scribes

Inaccuracies in Clinical Records

All practitioners are duty-bound to keep and maintain accurate clinical records of all their patient consultations. Failure to do so may lead to a practitioner being found guilty of unsatisfactory professional conduct or unprofessional conduct, which may result in conditions being imposed, or even suspension or cancellation of their registration as a health practitioner[3].

To ensure that clinical records are accurate, every clinical note that a practitioner drafts must:

- use a 24-hour time format, referring to and placing all relevant events and/or observations in chronological order[4]

- contain clear reasons for any diagnoses or treatment plans[5]

- refer only to objective information, keeping the author’s opinions limited to that based on what they actually observed or can inquire into, in light of the patient’s medical history[6]

- contain, and be updated with, accurate details of the patient’s medical history, including their pre-existing conditions and any medication(s)[7]

- document and record if and when the patient has given consent for treatment and/or any referrals that the practitioner may make on behalf of the patient[8], and

- make clear reference to any treatment plan and/or any other details that are necessary to support and facilitate the patient’s continuity of care[9].

Given these stringent requirements placed on practitioners, the Royal College of Australian General Practitioners (RACGP) has advised its members that, currently, AI medical scribes may not be capable of converting the transcription of a practitioner-patient consultation into a clinical note that complies with the above requirements.

Research suggests that most medical scribes, like most forms of Gen AI, are prone to “hallucination glitches”, where they malfunction and spurt out random text[10]. Many AI medical scribes also struggle to differentiate between speakers. They often confuse practitioners’ questions as patients’ answers in a consult, or may populate the records with a previously used term that is not appropriate. These errors could have serious consequences on the diagnosis or treatment of a patient.

These limitations pose serious risks for practitioners, who remain liable for any error in their clinical records.

Another limitation is that non-verbal clues are not captured by AI scribes.

Accordingly, AHPRA has advised all practitioners who use AI scribes to exercise great caution and vet every clinical note produced by the scribe before entering it into the patient’s file, or relying on it for any other clinical task[11].

Possible Breaches of Privacy & Patient Confidentiality

Practitioners have a duty to take reasonable steps to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their patient’s health data[12]. Gen AI programs usually own the data that the user feeds into the system, and sometimes share it with third parties. AHPRA has issued guidelines that require practitioners to obtain the informed consent of their patient before using an AI medical scribe. This requires a practitioner to:

- explain to the patient how and why the scribe would be used during their treatment, and

- explain whether and how the patient’s data would be shared with any third-parties.

It is also in the best interests of practitioners to:

- ask each patient for their consent to the use of a scribe at the beginning of every new consultation

- document and record if and when the patient gives consent to the use of an AI medical scribe, and

- ensure that the data fed into the AI system is de-personalised so that the patient cannot be identified[13].

If a practitioner accidentally includes a patient’s identifiable health data in an AI medical scribe or another Gen AI system, they have a duty under privacy legislation to inform the Privacy Commissioner[14]. Practitioners should also consider potential reputational risks resulting from accidental misuse if their reliance on AI programs places their patients at risk[15].

The Risks of Using AI Medical Search Engines

The Practitioner’s Duty of Care

Practitioners should exercise their own judgment to ensure that the information and/or sources that an AI search engine provides them with is:

- based on up-to-date medical advice or data

- relevant to the patient’s condition or complaint(s) that they are investigating, and

- published in peer-reviewed journals, or other widely-accepted reliable sources.

Practitioners expose themselves to claims of negligence if, by relying on AI, they give advice that is incorrect or poorly considered, in contravention of their duty to exercise reasonable care and skill in the provision of professional medical advice and treatment[16].

Expert Reports

In response to the inaccurate usage of GenAI tools in court procedures, most Supreme Courts of the states have issued guidelines or Practice Notes to ensure that the probative value of evidence used in such procedures is maintained.

For example, the Supreme Court of NSW has dictated that from 3 February 2025, Gen AI cannot be used to prepare expert reports unless prior leave has been obtained from the Court. Further, experts must attest that they have not utilised GenAI in their reports.

No accepted use: Large Language Models (LLMs) (eg ChatGPT)

Practitioners must never use an LLM to draft or embellish any of their records, regardless of the time-saving benefits. All records created by practitioners are legal documents that should reflect their own work, observations, and skills.

AHPRA’s guidelines clearly provide that practitioners should never fetter their skills to an AI for the sake of expediency, even for drafting correspondence and record-keeping[17]. Practitioners will be liable in negligence for any errors in clinical records, and the consequent impacts they have on the patient.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has instructed its members that Gen AI is never a safe place to store or upload sensitive patient data[18].

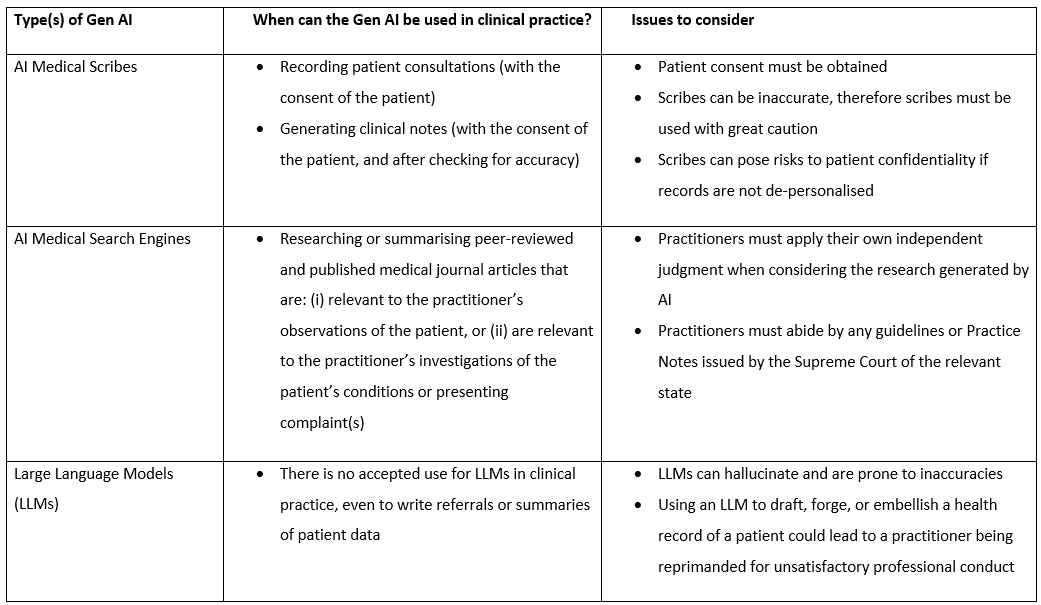

The following table highlights parameters for use and issues to consider when using Gen AI in healthcare.

Will Practitioners be Prosecuted for Misusing Gen AI?

In 2023, a West Australian nurse used ChatGPT to embellish a hospital discharge summary[19]. This was a serious case of unsatisfactory professional conduct, which prompted the executive of Perth’s South Metropolitan Health Service to ban the use of AI in all its hospitals. Its decision was based on the fact that if the summary was relied upon, and was inaccurate, the patient could have been given the wrong care and suffered serious injury.

The nurse in question was not prosecuted. However, the release of new guidelines about the use and misuse of AI in clinical practice suggests that regulators are now shining the spotlight on this conduct, and that prosecuting the misuse of AI will likely be a focus of regulators in the near future.

Conclusion

AI tools are here to stay and can revolutionise healthcare by improving diagnostic accuracy, aiding record keeping, and personalising care. However, integration into clinical practice must be approached with caution, sensitive to the issues of inherent limitations, patient data privacy, and potential misinformation or bias. It is essential that the practitioner provides continual oversight[20].

This article was written by Consultant Nevena Brown and Paralegal Josh Jones. For further information or advice on any related matters please contact Nevena.

Meet our Team

Meet our Team View our Insights

View our Insights